A Study in Style: John Updike vs. Joy Williams

Reflecting on the relationship between voice and content

Why do authors write the way they do? Why do they choose a certain type of syntax, patterns of sound, this word versus that word? Where does voice come from? And how much is intentional?

I suspect most authors write in a voice that sounds natural to them, just as we all have different types of personalities: the bold salesperson, the reserved accountant, the jokester, the analyst, the extrovert, the introvert. We don’t choose our personalities, and although we might be able to modulate in certain contexts, we are who we are.

Therefore, maybe it’s pointless to ask about an author’s style — we write how we write — yet as a reader I’m fascinated by syntax and the relationship between style and substance, voice and content.

We know what a hard-boiled detective novel sounds like. Terse sentences, sharp prose, wry humor. Does an author with a naturally terse style and wry sensibility gravitate toward writing detective novels? Or does an author drawn to detective novels develop an appropriate voice to the genre?

In other words, do you choose a genre appropriate for your voice, or do you cultivate a voice appropriate for the genre? Or do your voice and choice of genre come from some other mysterious source?

There’s no answer to these questions, but today I’m going to compare two stories with notable, and notably different styles to see if there’s anything we can deduce about the relationship between style and substance and where voice comes from.

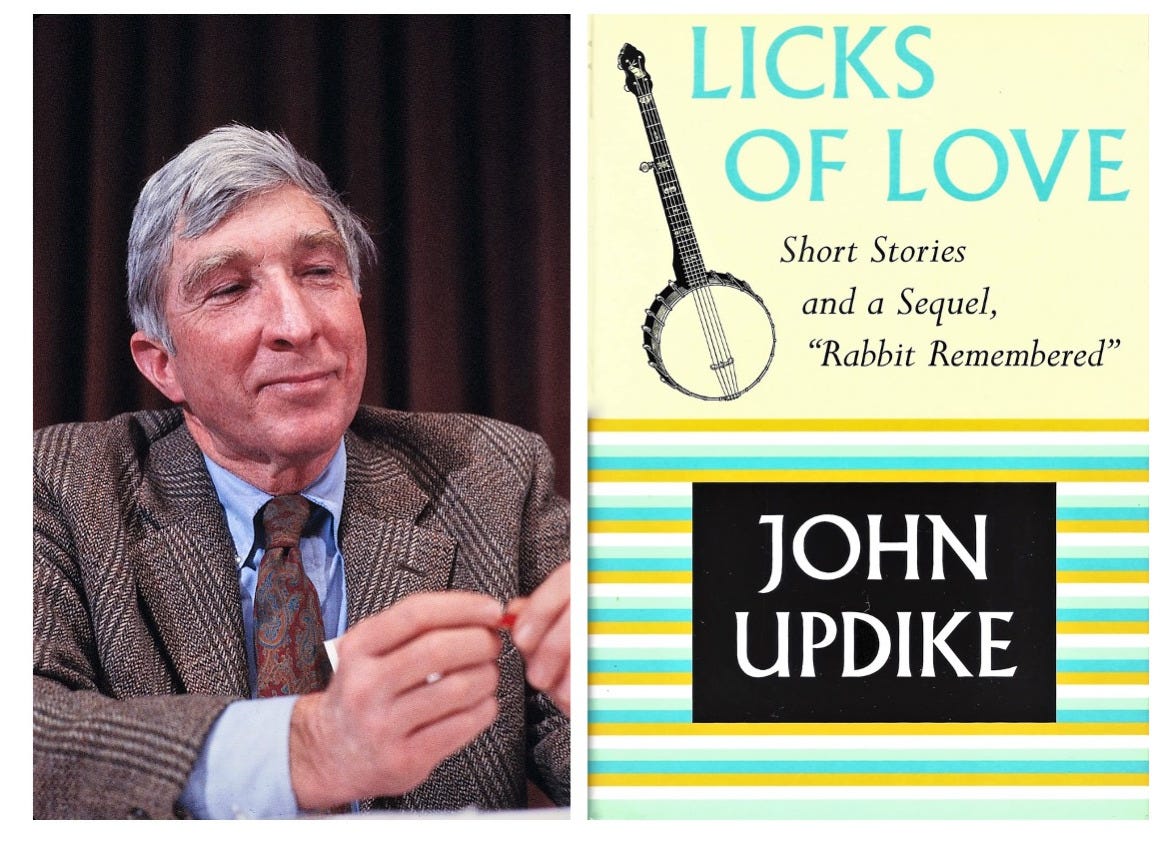

John Updike’s “Natural Color”

This story, published in Updike’s 2000 collection Licks of Love, is representative of the author in both style and substance. The story is about a late middle-aged man named Frank who, while walking down the street of his small New England town, spies an old lover, Maggie, with a new man.

Not wanting to confront her, he ducks into a drugstore and buys a random assortment of items. He remembers their affair, how they both stepped out on their spouses. Because they lived in a small community, their business was on display, and eventually Frank and his wife Ann moved to another town to keep their marriage intact.

Maggie left her husband and now, years later, has shown up in Frank’s new town, her red hair as fiery as ever. When he goes home, he doesn’t mention seeing her, but Ann also saw Maggie and brings it up. She needles her husband about his old lover and whether Maggie dyes her hair. In the end, we see Frank obviously has not gotten over his old flame but is trying to repress her.

This is a typical Updike story — a man of the Mad Men generation behaving badly but feeling conflicted about it, and the couple holding their marriage together because that’s what you do (or that’s what people of that generation did).

His content isn’t for everyone, but his style is well suited for his material. He tends to write long sentences with lots of asides, so the syntax mirrors the mind of an educated man with a conflicted heart. Here’s the first three sentences of “Natural Color”:

Frank saw her more than a block away, in the town where he had come to live, where Maggie had no business to be, and he had no expectation of seeing her. Something about the way she held her head, as if she were marveling at the icicled eaves of the downtown shops, sparked recognition. Or perhaps it was the way the low winter sun caught the red of her hair, so it glinted like a signal.

What to make of this prose? From a style point of view, why does Updike write these long (compound and compound-complex) sentences? We might describe the first sentence as a cumulative compound sentence:

Independent clause: “Frank saw her more than a block away”

Cumulative dependent clause: “in the town where he had come to live”

Cumulative dependent clause: “where Maggie had no business to be”

Cumulative independent clause: “he had no expectation of seeing her”

The second sentence is a complex sentence with the dependent clause spliced into the independent clause:

Independent clause subject: “Something about the way she held her head”

Dependent clause: “as if she were marveling at the icicled eaves of the downtown shops”

Independent clause predicate: “sparked recognition”

Frank is conflicted: He loves Maggie but he’s committed to his wife. He’s excited to see her but also wants to avoid her. The back-and-forth syntax mirrors his state of mind. The syntax also pulls the reader through by creating tension. The sentences raise questions that we want answered: We know Frank and Maggie have a history, but what was it? Why would he think she has no business being here? What is her red hair signaling to him?

The prose also delivers an intriguing combo of specificity (“the icicled eaves of the downtown shops”; “the low winter sun”; the red hair that “glinted”) and mystery (“Something in the way”; “Or perhaps”).

The sense of doubt from words like “something” and “perhaps” read like the artist trying to dig in and find the answers himself, as if Updike the writer is thinking, There’s something about the way Maggie holds her head that catches Frank’s eye. Or, no, maybe it’s her red hair. He’s seeing her from a distance but is drawn to her magnetically. Hmm. We can’t say that was his thought process as he wrote this story, but his style sounds like the thought process of an author striving for the precise description.

One other passage caught my eye, a flashback to when he and Maggie were discussing their future:

“You have anything better to offer?” Maggie had once challenged him, having pinched her lips together and decided to take the leap. Her eyes in this moment of daring had been round, like a child’s.

He felt attenuated, strained, answering weakly, “You know I’d love to be your husband. If I weren’t already somebody else’s.”

If you turned this story in for a writing workshop, a teacher might strike the line “He felt attenuated, strained, answering weakly.” A teacher or editor might suggest you pick one or the other of “attenuated” and “strained,” or might recommend deleting the adverb “weakly.”

He would be simpler to say, “He felt strained and answered…” but this would be much less satisfying to read. Having both words — “attenuated, strained” — again feels like Updike the author reaching for precision. Frank doesn’t feel “attenuated and strained.” The comma between them reads as if Updike is thinking, He felt attenuated. No, maybe he feels strained. Or maybe both.

That sense of doubt, that struggle for precision, matches the emotional moment for the character, who can only answer “weakly” that he feels two things at the same time. Style and substance are in harmony.

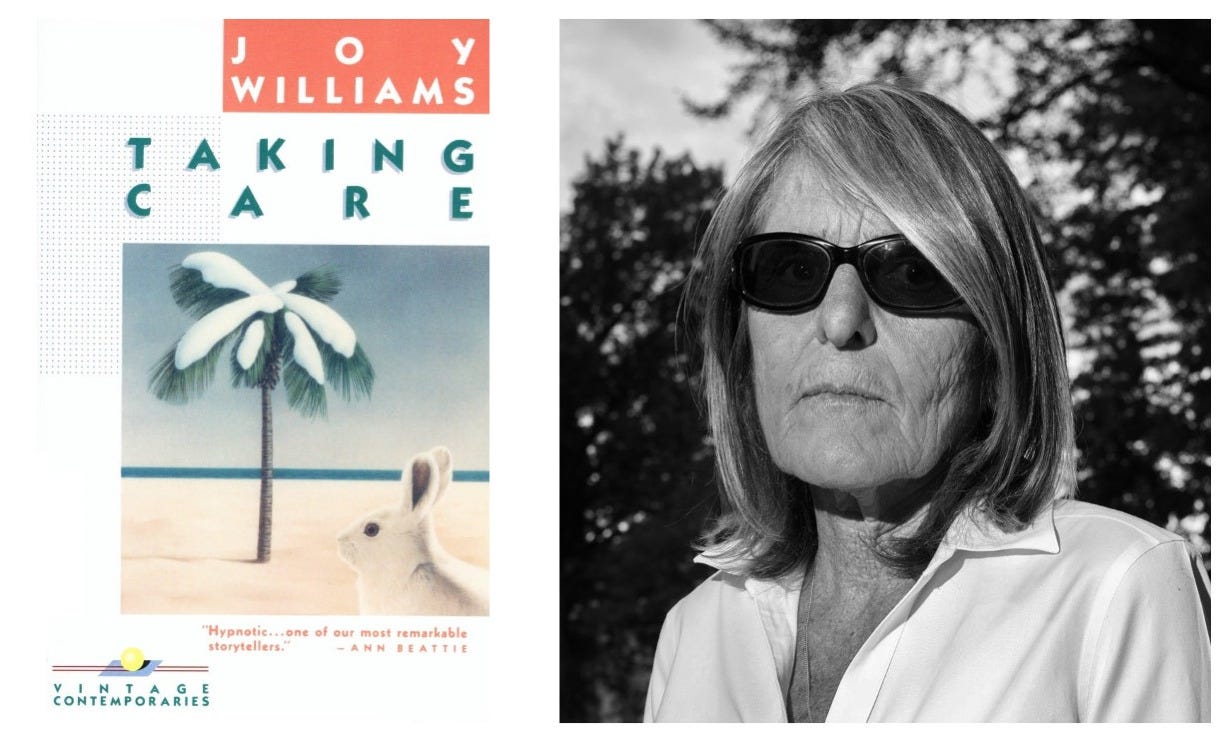

Joy Williams’s “The Farm”

Williams has a much different approach to style, but with content in the same league if not the same ballpark. Published in the seventies, “The Farm” is about a 30-something couple in New York. Tommy works in the city (and is living the Mad Men lifestyle, possibly having affairs and modulating his drinking), whereas Sarah lives in the suburbs, raising their young daughter largely on her own.

One summer night, the couple hires a babysitter and attends a series of parties. Tommy is not drinking this weekend, but Sarah has a few glasses of wine. She drives them from one party to the next, and in transit she accidentally hits a young hitchhiker on hallucinogens. Tommy, sober, tells the police he was driving, and they chalk it up to an accident. The victim had been on hallucinogens and was hitchhiking.

After the accident, we see their marriage in flux. They bicker and then make love while spending a night at a hotel in the city. Tommy takes their daughter to church. Sarah tries to quit drinking. Then she gets a call and then a visit from the young hitchhiker’s mother, Genevieve. The woman, an old local to the town Tommy and Sarah temporarily live in, comments on their house. When Sarah tells Tommy about the visit, he tells her not to speak to the woman again.

But then when he’s out with their daughter, Genevieve comes for another visit. She comments about Sarah having a drink, which makes us wonder if she intuits Sarah had been the one behind the wheel when Genevieve’s son was killed. Then she says she would like to take the daughter out for a movie sometime. Sarah feels entangled with this woman, as if she owes her a relationship with her daughter for taking her son.

Tommy comes home and asks why they locked the door. Sarah replies, “There are robbers. Everything has changed.”

The story is unsettling, made more so by the style. Williams leans on punchy, declarative, “just the facts, ma’am” sentences, as if the trauma can only come out one quick clause at a time. Here is an excerpt from the paragraph right before she hits the hitchhiker:

Sarah at last fell silent. The road seemed endless as in a dream. They seemed to be slowing down. She could not feel her foot on the accelerator. She could not feel her hands on the wheel. Her mind was an untidy cupboard filled with shining bottles. The road was dark and silvery and straight.

Unlike Updike’s protagonist, who is vacillating between one desire and another, Williams’s character’s mind is “an untidy cupboard filled with shining bottles.” She’s not conflicted in her desire, but she is trying to account for her actions. She’s about to kill a man, an event she can barely face. Rather than dwell endlessly on this or that possibility, with this or that cumulative clause, the story is stark. One clause at a clip. This happened. Then this happened. Then this happened.

Here's another passage:

Sarah stopped drinking immediately after the accident. She felt nauseated much of the time. She slept poorly. Her hands hurt her. The bones in her hands ached. She remembered that this was the way she felt the last time she had stopped drinking. It had been two years before.

Why is the story written like this? You could combine a few sentences to say, “She slept poorly, and the bones in her hands ached. This was how she felt the last time she stopped drinking two years ago.” But this revision doesn’t have the same psychological punch. It’s news reporting rather than the relentless boom-boom-boom of those short sentences.

The style matches the substance — a woman confronting trauma, one clause at a time. Which brings me back to my original question: Is it Williams’s natural voice to have these punch sentences? And does she naturally choose subject matter suited for that voice?

In other words, is there a connection between the way the world sounds to an author (a voice) and the way the world looks (the content)? Do authors choose material for a voice or choose a voice for the material? Or, more likely, are both voice and content the twin expressions of something unconscious?

And what is that?