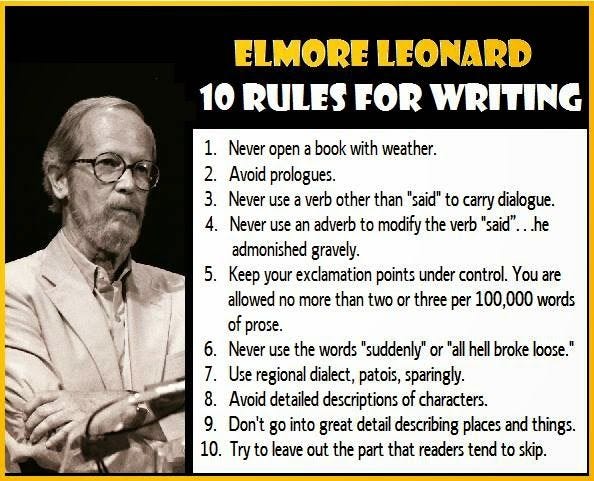

Elmore Leonard has a famous set of 10 rules for writing that he laid out about 25 years ago. The list might have been a little nod to his novel, Swag, in which one of the characters has a set of 10 rules for criminals. The character breaks the 10th and most important rule: “Never associate with people known to be in crime.” Oops!

Leonard says his most important rule is his 10th: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.” I’d say he follows this rule well, but he also breaks a lot of the rules you’ll hear from the gurus of publishing. I presume editors, literary agents and others lay out rules like “your book has to start fast” or “you need a consistent POV” because they’re inundated with manuscripts that break said rules.

The very best books, however, tend to do things you’re not supposed to do, so as a counterbalance to all the experts on the internet, here are some “rules” that Elmore Leonard often breaks, using his novel Riding the Rap as an example.

Do you need a high concept?

Literary agents always seem to be asking for something with a “high concept,” by which I think they mean a book where the premise sounds big and new and exciting. Think old-school summer blockbuster:

“Great white shark terrorizes a New England town at the height of summer tourism.”

“When aliens invade, a scientist, a soldier, and a ragtag group of crop dusters have to save the planet.”

“Scientists create a dinosaur theme park — but then they get loose!”

The idea behind these movies — Jaws, Independence Day, Jurassic Park — captures your imagination in a line. They make you stop and say, “Oh, that sounds great!”

Nothing wrong with that, but Elmore Leonard never really had what I would call a “high concept” novel. Each of his books takes a simple enough premise — a heist, a kidnapping, a jailbreak — followed by 300 pages of zany characters bumping into each other.

Riding the Rap, for instance, is about a bookie named Harry who sends a Puerto Rican named Bobby to collect from a no goodnik named Chip who is mooching off his elderly mother in South Florida. Chip and his right-hand man, a Bahamian named Lewis Louis, convince Bobby to switch sides and kidnap Harry for some ransom money.

They enlist the help of a psychic named Reverend Dawn to nab Harry. Then Harry’s ex-girlfriend, an ex-stripper named Joyce, gets her new boyfriend, U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens, to investigate. The novel then bounces around between Raylan’s investigation and the somewhat hapless criminals holding Harry hostage.

Is that “high concept”? Everyone is a little off-beat, but there are no high stakes here. The world isn’t going to end if they don’t find Harry in 24 hours, and there’s not a great one-sentence, summer blockbuster-style tagline. Instead, if this were a movie, it would be an old Wes Anderson art-house feature or the B-side Coen Brothers screwball comedy Burn After Reading.

Maybe an ordinary book with a lower concept premise is just fine.

Do novels need to start fast?

Another chestnut from book people is some variation of “get the action going on page 1.” This is generally good advice because beginning writers tend to have a lot of throat-clearing in chapter 1:

Lengthy descriptions of the character or setting

Pages and pages of back story

A character sitting around thinking about stuff, maybe while walking the dog or driving around

An introduction of the present-time and then an immediate scene in memory

I imagine agents and book editors get endless pitches where chapter 1 should be cut, so they preach the gospel of “get the action going on page 1.” A car crash. A kidnapping. A character screams as he’s held by his ankles from a high balcony.

Action, action, action.

Chapter 1 of Riding the Rap opens with Raylan picking up a prisoner in Ocala, Florida, and transporting him back to Palm Beach County. Because he doesn’t have a partner, he makes the prisoner, Dale Crowe Junior, drive a confiscated Cadillac—and he threatens to put the prisoner in the trunk if he talks too much.

This opening does follow the spirit of the rule in that it drops us into a compelling present-time scene, and it also does a nice job of introducing Raylan as a modern-day Western lawman.

However, the opening chapter isn’t particularly action-packed. Dale makes an attempt to escape, which Raylan quickly foils. Then some other dudes try to carjack them, and once again Raylan quickly foils the plot and delivers Dale and the two dudes to the jail in West Palm.

While this episode is compelling, Dale Crowe Junior has nothing to do with the main plot of the novel. Chapter 1 reads like a standalone short story, but who cares? It’s fun and compelling even if the book doesn’t cohere with a single arc.

Do you need a consistent point of view?

One more “rule”: Most book people (myself included) recommend coherence in point of view. Plenty of novels rotate among a cast of characters (rotating third POV), but the pros tend to limit it to three or four points of view, with chapter breaks signifying a shift in perspective.

In other words, Chapter 1 is about Character A, Chapter 2 is about Character B, and so on. You might have a pattern like A-B-A-B-C-A-C-A-B-C, where each character gets an even amount of stage time and shows up at regular intervals.

Leonard breaks this “rule,” too. In the opening three chapters of Riding the Rap, he gives us the interior point-of-view thoughts of:

A pair of cops delivering the fugitive

Dale Crowe Junior

Raylan Givens

Back to Dale

Back to Raylan

Back to Dale

Harry Arno

Bobby Deo

Chip Ganz

Back to Bobby

Louis Lewis

I might have missed one in there, but that all happens in 30 pages. It reads like a television show, incoherent if you want a story about someone’s consciousness but breezy and readable if you’re looking for something to escape with.

Do you need to “write what you know”?

Leonard grew up in the 1930s, served in the Navy, went to college, and then worked as an advertising copywriter until he made enough money to write fiction full-time. He started with Westerns, which were popular in the fifties and sixties, and then he shifted to crime fiction when the Western market dried up.

What did he know about crime, kidnapping, strip clubs and the U.S. Marshals? Did he “write what he knew” in Riding the Rap?

I suppose he knew about greed, and the way people tend to come up with hare-brained schemes, and how a lot of schemes don’t work out. I presume he also spent enough time in Florida to make the vibe believable. Does that satisfy the rule for “write what you know”? Or did he just ignore that advice because nobody wants to read about a copywriter on deadline?

Conclusion: The Rules

As a fiction writer, your job is to be interesting and to make your world believable. Arguably, making your world believable is half the battle, as readers find it interesting to encounter something relatable on the page.

To wrap up, I’ll come back to Leonard’s rule #10: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.” All the other “rules” about concept and concept and point of view are window dressing. As long as your fiction is interesting, you can do anything you want.

So interesting! Thanks, Jon!!