I’m nervous to write about Flannery O’Connor. I have been reading and rereading her since high school, so she has this mythic weight in my mind, as well as casting a long shadow over the Southern literary tradition.

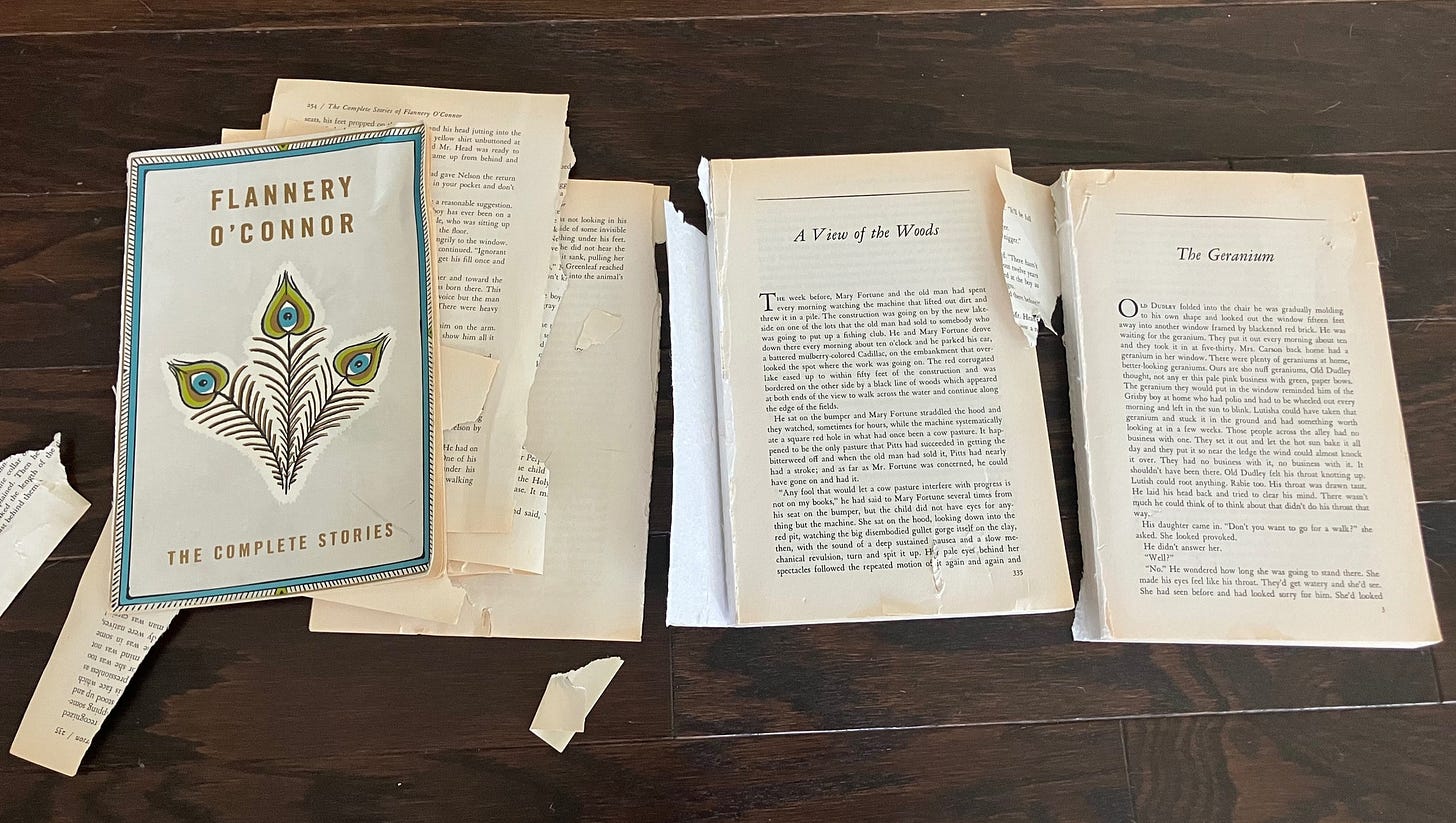

However, while I was preparing this essay, my dog destroyed my 25-year-old copy of her collected stories. The mauled book almost looks like the ending of an O’Connor short story, so I can’t put this off any longer. I have too much to say, however, so this post is essay 1 of three.

I’ll say here in this general throat-clearing that my reread of her this year is the first time I’ve revisited her in my 40s. I have outlived her now, a fact that shapes my read on her this go-round.

In the Ethan and Maya Hawk film Flannery, Maya portrays her as an early-20s aspiring writer. This version of Flannery is closer in age to my daughters than to me, and listening to this interview with the Hawks, I now identify more with the father than the daughter. I hear in Maya’s commentary the energy and earnestness but also the hubris of youth.

This is a longer essay for another day, but what I mean by the “hubris of youth” is not hubris in the sense of “I’m so great,” but rather a lack of experience with the day-to-day realities and thus the consciousness of other human beings. In other words, the confidence born of inexperience: “Isn’t this interesting?” “Have you ever thought of this?”

Well, yes. There’s still plenty of mystery to life on the older side of 40, but it’s not the same kind of mystery you experience when you’re young. The questions change, and I’m finding fewer and fewer answers in literature.

That’s one paradox of being an artist: The desire to create is rooted in the belief that what you have to say is interesting. I have a half-baked idea that the best artists find ways to reveal how the mind works rather than focusing on specific conclusions about life. It’s a subtle distinction between “This is on my mind” versus “Let me tell you how it is.” Or: “This is what I see in the world” versus “This is how the world is.”

O’Connor’s mind is interesting enough to write books about. She clearly had the desire to create, but if she was trying to tell you anything, it was a message from outside herself. One aspect of O’Connor I glossed over as a younger man — still dazzled by her skill as a writer and the outlandishness of her stories — is the literalness of her Catholicism.

In Mysteries and Manners, she wrote about an English professor insistently asking her about the symbolism of a man wearing a black hat, to which she insistently replied that the significance of the hat is, “Most countrymen in Georgia wore black hats.” She told people time and again what her point was in writing the way she does, and a tour of a few stories might point toward why some critics haven’t listened.

“The Life You Save May Be Your Own”

How do you entertain a 17-year-old boy in an English class? How about the story of a ne’er-do-well swindling an automobile out of a woman who is trying to marry off her disabled daughter?

The ne’er-do-well is a drifter named Shiftlet who shows up at a house in the country, where an old woman and her grown deaf daughter live. He works on the farm a few days, agrees to marry the daughter, and heads off in the woman’s car for what is supposed to be their honeymoon. Instead, he drops his bride off at a roadside diner and drives off into a storm.

The opening pages are a great study in description and dialogue. When Shiftlet shows up, “The old woman didn’t change her position until he was almost into her yard; then she rose with one hand fisted on her hip.” What a great word: fisted! O’Connor then tells us the woman “was about the size of a cedar fence post.” I love the specificity of cedar, but the strangest detail comes later, when Shiftlet offers her a piece of gum, and “she only raised her upper lip to indicate she had no teeth.”

So, this man Shiftlet has come upon a widowed old toothless woman out in the country and her grown deaf daughter, and he notices they have an automobile. “You ladies drive?” he asks. At this point, a sophisticated negotiation begins. We know pretty fast that Shiftlet wants his hands on that automobile, but the surprise comes when this old woman shows she has some designs of her own. But first, she introduces herself and asks what he’s doing here. Rather than replying:

He judged the car to be about a 1928 or ’29 Ford. “Lady,” he said, and turned and gave her his full attention, “lemme tell you something. There’s one of these doctors in Atlanta that’s taken a knife and cut the human heart — the human heart,” he repeated, leaning forward, “out of a man’s chest and held it in his hand,” and he held his hand out, palm up, as if it were slightly weighted with the human heart, “and studied it like it was a day-old chicken, and lady,” he said, allowing a long significant pause in which his head slid forward and his clay-colored eyes brightened, “he don’t know no more about it than you or me.”

At this point, we understand Shiftlet wants the automobile, and this speech is the beginning of his sales pitch. Like a good salesman, he uses repetition (“Lady”), the way a salesperson will repeat your name over and over to build familiarity. A few paragraphs later, he continues:

“Lady,” he said, “nowadays, people’ll do anything anyways. I can tell you my name is Tom T. Shiftlet and I come from Tarwater, Tennessee, but you never have seen me before: how you know I ain’t lying?”

One technique of sales is to knock down objections, which is what Shiftlet is doing here — how is she to know he’s not lying to her? Why, would a liar come out and admit he could be lying? Of course not! (Of course he would.)

The next step in the negotiation:

“Lady,” he said, “people don’t care how they lie. Maybe the best I can tell you is, I’m a man; but listen lady,” he said and paused and made his tone more ominous still, “what is a man?”

The old woman began to gum a seed. “What you carry in that tin box, Mr. Shiftlet?” she asked.

“Tools,” he said, put back. “I’m a carpenter.”

Now we know the woman wants something, too! Earlier, we learned she had no teeth, which comes into play as she gums a seed. But that’s not an idle gesture. It’s a pause for her to contemplate what to say. Rather than answer her question and stay on track, she changes the subject, taking the upper hand in their power dynamic.

The Literal Grace of God

He wants the car, and to milk her for money. She wants to marry off her daughter, and to have a man around to help on the farm. In the end, it seems like he wins when he deposits the girl and makes off with the car, but this being Flannery O’Connor, he’s compromised his soul. The ending reads as though God himself is coming down with tornadoes in retribution:

A cloud, the exact color of the boy’s hat and shaped like a turnip, had descended over the sun, and another, worse looking, crouched behind the car. Mr. Shiftlet felt that the rottenness of the world was about to engulf him. He raised his arm and let it fall again to his breast. “Oh Lord!” he prayed. “Break forth and wash the slime from this earth!”

The turnip continued slowly to descend.

The irony, for Shiftlet, is that he is the slime. Double irony because God appears to be answering his prayer. This isn’t particularly subtle (his name is Shiftlet, as in shifty), but as O’Connor says in Mystery and Manners, about being a Catholic novelist:

When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal ways of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock — to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.

Until this year, I’m not sure how literally I took her, but now I’m convinced she meant precisely what she said. Rather than symbolism or metaphor, the turnip-shaped clouds might be the literal “large and startling figures” that come if you reject the grace of God.

Stay tuned for part two next Friday.

Silly Maeve puppy!!! Great essay - look forward to part 2