Years ago I heard a professor describe Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove as 300 of the most boring pages ever written followed by 100 pages of absolute splendor. I’ve never made it through the 300 boring pages to confirm, but I believe I know what the professor was getting at.

This week, I’m analyzing two stories I didn’t particularly enjoy for the first ¾, but whose endings were knockouts. As we’ll discuss, George Saunders’s “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” and Jhumpa Lahiri’s “A Temporary Matter” don’t have much in common, but their endings will make you say, “Wow!”

George Saunders, “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline”

To start with Saunders: This author has a reputation as the nice guy of contemporary fiction. He got his start writing satirical, absurdist stories in the nineties, and by the 2010s he’d rocketed up to appearances on evening talk shows.

I’ll go ahead and say, since Saunders is super-duper famous and as successful as an author gets, that I’ve never fully trusted the nice guy schtick, precisely because it reads as a schtick, whereas his fiction can be chilly and detached. Which brings me to “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline.”

The story, originally published in 1992, is set in a fictional Civil War theme park, in a somewhat alternative reality where ghosts walk among us and roving gangs are terrorizing American businesses. The park is suffering financially, as tourists and investors have pulled out due to gang activity.

The narrator is the operations guy and second in command to Mr. A, and his job is to help put a stop to the attacks. When he discovers the new hire, Sam (hired to be a butter churner), might have been a war criminal in Vietnam and has excellent marksmanship scores, the narrator and the boss put Sam on security.

He starts by murdering some trespassing gang members, which is great as far as the narrator is concerned, but he quickly moves on to more innocent targets. When a boy is caught stealing some penny candy out of the gift shop, Sam hides the body but leaves the boy’s hand on Mr. A’s. The narrator becomes complicit in Sam’s crimes when he buries the hand instead of calling the police.

Things continue to devolve; the narrator’s wife leaves him when Sam commits violence in front of their sons; then Sam murders some teenagers who wandered onto the property; and then investors pull out, dooming the park.

Mr. A decides to torch the place for the insurance money. With the park erupting into flames, the narrator flees. On his way out, he stumbles over the ghost of the murdered boy, missing a hand, and then he runs into Sam, who is tying up his own loose ends. Sam stabs the narrator to death, and the story ends with the narrator’s soul rising above his body and watching the events with newfound understanding.

When the Veil of Satire Lifts

You can probably tell from this short summary that “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” is a strange story, driven by style as much as content. The prose — satirizing corporate-speak and the casual cruelty of the business world — is amusing in places, but I found it tiresome after a couple of paragraphs. Here’s a representative excerpt:

Next evening Mr. A and I go over the Verisimilitude Irregularities List. We’ve been having some heated discussions about our bird-species percentages. Mr. Grayson, Staff Ornithologist, has recently recalculated and estimates that to accurately approximate the 1865 bird population we’ll need to eliminate a couple hundred orioles or so. He suggests using air guns or poison. Mr. A says that, in his eyes, in fiscally troubled times, an ornithologist is a luxury, and this may be the perfect time to send Grayson packing.

You can see from this short passage how the business world forces us to make moral compromises (whether slaughtering birds or firing dedicated employees) and how language launders immorality and promotes cowardice (the “Verisimilitude Irregularities List” makes these compromises sound official and therefore reasonable).

Maybe it’s my vantage from 2025, but reading 15 pages of this was a chore. The narrator is an unlikeable cog in an immoral system until the last paragraph, when he gets hacked to death:

Possessing perfect knowledge I hover above him as he hacks me to bits. I see his rough childhood. I see his mother doing something horrid to him with a broomstick. I see the hate in his heart and the people he has yet to kill before pneumonia gets him at eighty-three. I see the dead kid’s mom unable to sleep, pounding her fists against her face in grief at the moment I was burying her son’s hand. I see the pain I’ve caused. I see the man I could have been, and the man I was, and then everything is bright and new and keen with love and I sweep through Sam’s body, trying to change him, trying so hard, and feeling only hate and hate, solid as stone.

This reminds me of the revelation at the end of Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” when the Misfit says of the grandmother, “She would’ve been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

Saunders’s narrator is unlikable and unreliable, but in the end the veil of satire lifts, and Saunders presents something honest about the world as reliability wobbles in. It’s an astonishing moment of heart in an otherwise chilly story.

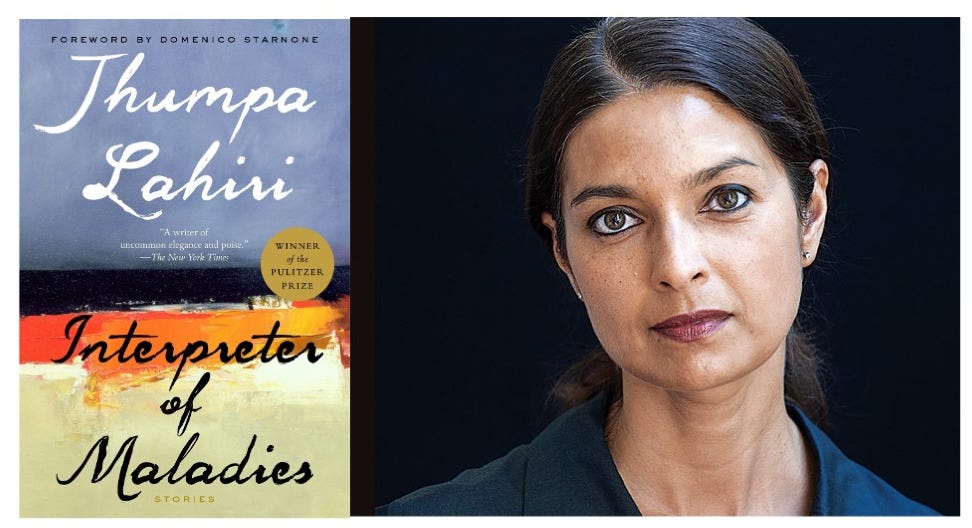

Jhumpa Lahiri’s “A Temporary Matter”

It might be unfair to pair Lahiri with Saunders because they are such different writers. The only things they really have in common are being contemporary and extremely well-known for their short fiction. I pair them because, whereas Saunders has this ironic veil that lifts in the end, Lahiri is earnest almost to a fault in “A Temporary Matter” — until the end.

“A Temporary Matter” is about an early-30s Indian-American couple in Boston. Six months ago their first child was stillborn (they never learned the sex), and now they have thrown themselves into their respective work: the wife Shoba as a proofreader for a publisher and the husband Shukumar as a Ph.D. student struggling to finish his dissertation. They spend their evenings in separate rooms, at a standstill in their marriage.

When the story opens, they get a letter from the power company saying that their electricity will be turned off for one hour each evening for a week while the company makes a repair. Over this week, the couple eats dinner together over candlelight and reconnects.

The wife suggests a game where they tell each other something they have never told before, and each night they make their minor confessions: she rifled through his address book when they first met, and he once forgot to tip a waiter. They dance around the unsayable: when she’d gone into labor, he’d been traveling and arrived too late. The baby was dead.

Their nights together this week are told in lush prose:

The next night Shoba came home earlier than usual. There was lamb left over from the evening before, and Shukumar heated it up so that they were able to eat by seven. He’d gone out that day, through the melting snow, and bought a packet of taper candles from the corner store, and batteries to fit the flashlight. He had the candles ready on the countertop, standing in brass holders shaped like lotuses, but they ate under the glow of the copper-shaded ceiling lamp that hung over the table.

Unlike Saunders satirizing corporate-speak, Lahiri gives us these characters’ hearts and paints a vivid scene of their evenings together, piling up details about the bay leaves and cloves in their stew, and in this scene, “Something happened when the house was dark. They were able to talk to each other again.”

You might guess from the title where this is going. On the final night, the power company sends a second letter saying they’ve completed the work and there will be no outage. Shukumar is disappointed, but Shoba says he can light the candles anyway.

After the candle burns out, Shoba turns on a light and says gently, “I want you to see my face when I tell you this.” She’s found an apartment and is leaving him. Every night, while he thought they were reconnecting, she’d spent the day searching and signing a lease: “It sickened Shukumar, knowing that she had spent these past evenings preparing for a life without him.”

When it’s his turn to speak, he stabs her (metaphorically). He tells her that he had returned in time for the birth last fall, and had held their dead baby in his arms in the dark, and it had been a boy. She never knew any of that until now. Would it have made a difference if she’d known it earlier? I don’t know, and Lahiri doesn’t offer any hint.

In the end, Shukumar clears their plates, and Shoba turns off the lights. “She came back to the table and sat down, and after a moment Shukumar joined her. They wept together for the things they now knew.”

Clear Eyes, Full Hearts

Whew.

Graham Greene once said that “all writers must have a splinter of ice in their hearts so that they can be involved in the world and also slightly removed, making observations.”

Until the last two pages, I thought the Lahiri story was fine but a little overwrought. For instance: “Shukumar took out a piece of lamb, pinching it quickly between his fingers so as not to scald himself. He prodded a larger piece with a serving spoon to make sure the meat slipped easily from the bone.”

Reading this, I kept thinking, “She’s so earnest.” But then she takes that little sliver of ice in her heart and shivs you with it. It turns out that all those lovely descriptions of the candles and the bay leaves and such were just to disarm you.

Whereas “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” is 15 pages of chilly absurdism and one paragraph of heartfelt splendor, “A Temporary Matter” is 15 pages of heart-on-your-sleeve prose followed by two pages of unflinching narration.

Of the two, I suspect the Lahiri story will stick with me longer, but they’re both worth reading. Unlike Wings of the Dove, neither story asks you to slog through 300 pages of Jamesian prose to get to a stunning revelation.

I agree with Heather. Excellent insights, as always!

Terrific analysis, as always -- thanks, Jon!