Last week I wrote about the question of who the narrator is in the third-person point of view (POV). We looked at metafiction in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones and Ian McEwan’s Atonement, in which the third-person narrator broke the fourth wall and revealed themselves.

Most books written in the third person don’t have that metafictive element. Nevertheless, there usually is a narrative presence or voice in control of the story, like the stage manager of a play or the camera person in a film. Today, I’ll dig into how the invisible narrative presence operates and what it can do with a story.

Registers of Perspective

Speaking from my own experience, I bet many authors don’t know where their narrative voice comes from. It may be the subconscious (or unconscious) speaking, but voice feels like something separate from myself as an author, something I don’t have full control over. I therefore call what I’m talking about the “narrative presence” or “voice” rather than an explicit “narrator” (which implies a specific character) or the “author” (which can be misleading).

Whatever we call it, this narrative presence is in control of the “register” of a scene. A register is a combination of voice and perspective — the way the “scene” is staged. You could have a high register with a zoomed-out omniscient voice telling a tale, or the low register of characters engaging in hijinks in a bar.

Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V offer a concrete example on the stage. We see Henry as Prince Hal joking around with Falstaff in a low register, and then we see him giving a high-register speech to the troops as king. The register encompasses the scene (the bar versus the battlefield), the characters (drunks versus soldiers), the diction (joking versus sober), etc.

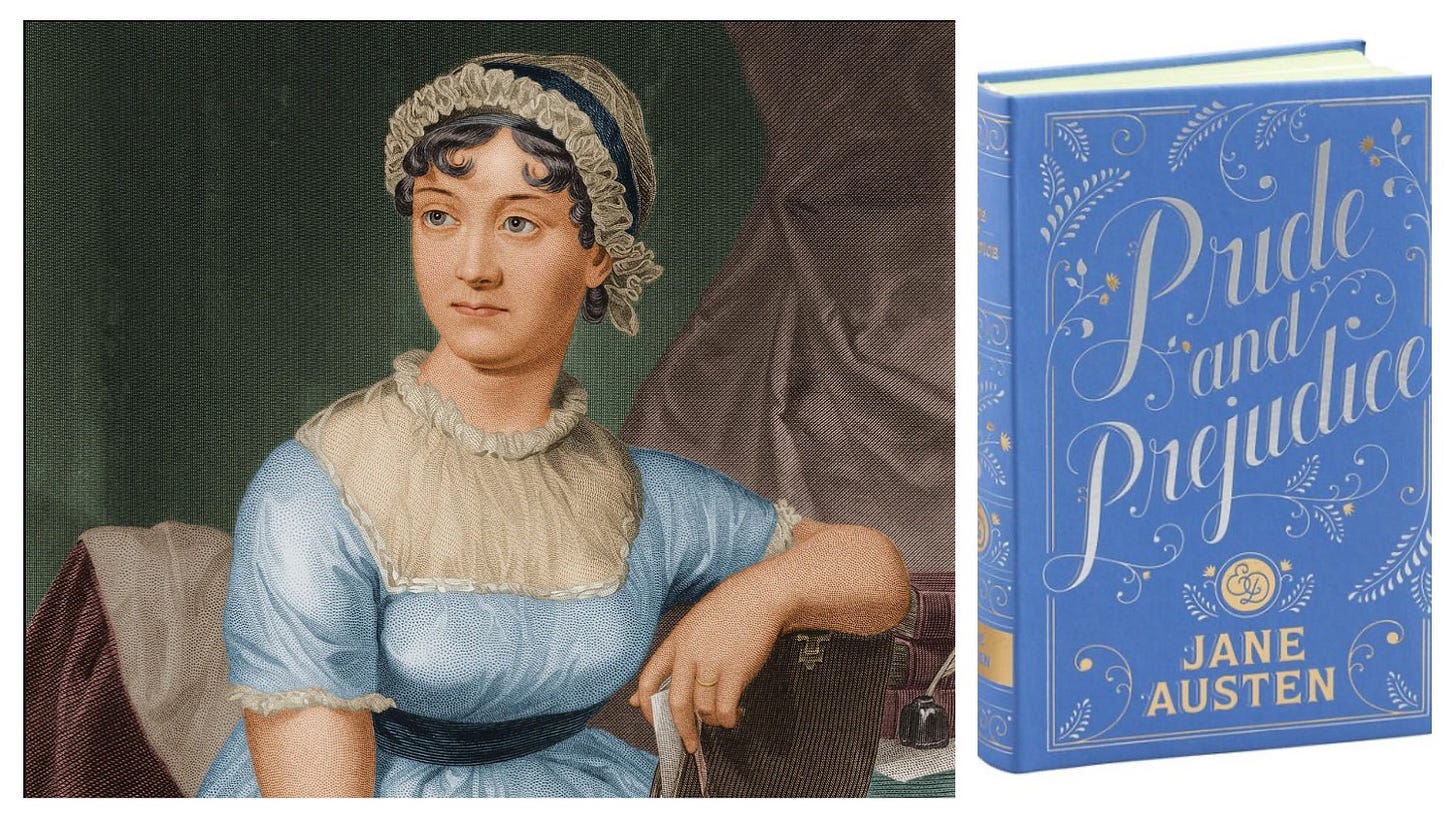

In fiction, the narrative presence serves a kind of stage-managing role via elements of voice (diction, syntax), mood, character, and perspective (whose mind we’re in and how close we are). To explore this, below are brief analyses of Pride and Prejudice and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Narrative Irony: Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice

Jane Austen is a fine place to begin a study of point of view. She was a near-contemporary of Fielding but feels like a leap forward in the development of narrative technique. She is sometimes credited with inventing “free indirect discourse,” which is the fancy term for when a third-person narrator slides into a character’s thoughts without explicitly indicating it.

Let’s start with her narrator, who, unlike Fielding’s, never reveals herself with an “I.” Pride and Prejudice has one of the most famous first lines in all of literature: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Who is speaking here? Somebody is making this observation. You could make the case that the opening is from the town’s perspective, that it is the gossipy wives who all have this belief about rich and single men. Does the second sentence support this reading?

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighborhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

These opening lines describe the mood of the village as Mr. Bingley and then Mr. Darcy become the bachelors du jour. As the novel progresses, however, our hero Elizabeth Bennet comes into focus, and the book slides into her mind. To pull one random passage, here is the opening to Chapter 33:

More than once did Elizabeth in her ramble within the Park, unexpectedly meet Mr. Darcy.—She felt all the perverseness of the mischance that should bring him where no one else was brought; and to prevent its ever happening again, took care to inform him at first, that it was a favorite haunt of hers.—How it could occur a second time therefore was odd!—Yet it did, and even a third. It seemed like willful ill-nature, or a voluntary penance, for on these occasions it was not merely a few formal enquiries and an awkward pause and then away, but he actually thought it necessary to turn back and walk with her.

You can hear in these lines the uplifted manic heart of a young woman who might not yet realize she’s falling in love. The prose slides away from the stately judgmental “big” narrator from the beginning and into Elizabeth’s mind.

The interplay between those two narrators (the narrative presence and Elizabeth’s consciousness) creates some of the drama in the book. On one level, this passage wouldn’t be as titillating if it were from a stately old and cold narrator. Bringing us into the mind of Elizabeth makes the narrative feel warmer, more human, and more exciting. However, it might be claustrophobic if the entire story were in Elizabeth’s mind. The external narrator can comment on the actions and even poke a little fun at the characters.

Austen’s unacknowledged narrator almost allows you, the reader, to become the narrator, like a first-person role-playing video game. When you play a video game, you know you’re not the hero, but you’re running the controls, which allows you to escape into the player, almost as if you are in fact the hero.

Likewise, when Austen’s smart narrator makes a witty observation, we smile because we’re in on the joke and feel almost as if we made the joke ourselves. When the author is doing her job correctly, we become an active participant in the drama. We might “identify” with this anonymous narrator the same way we might “identify” with a character when the narrative slides into her mind. That’s quite a narrative feat — and might help expand our worldview, which is theoretically what fiction does best.

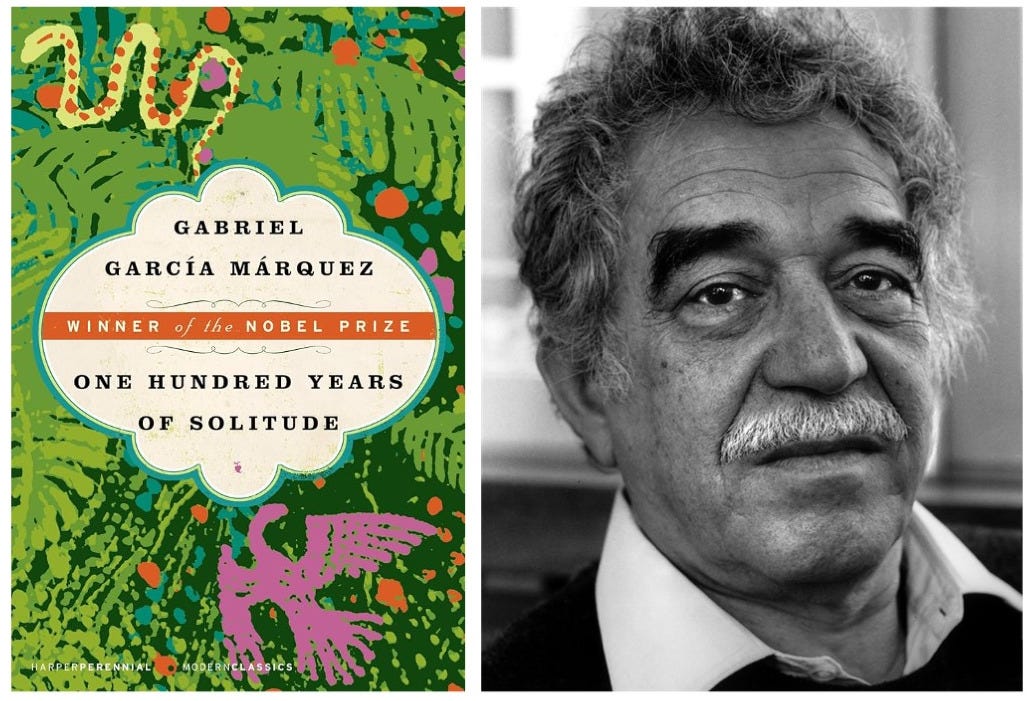

Complex Narration: Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude

This novel tells the story of five or six generations of the Buendía family. To match the story’s breadth, Garcia Marquez gives us a big omniscient narrator who zooms around in time with abandon, telling us more than any one character could possibly know. Take the opening, for example:

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs.

As with Austen, Garcia Marquez’s narrator stays hidden, but it shows us the interior lives of the characters a step deeper than you find in Austen. One lively example comes toward the end, when Aureliano Segundo’s wife, Fernanda, cracks and delivers a rant for the ages:

And while the urgencies of the pantry grew greater, Fernanda’s indignation also grew, until her eventual protests, her infrequent outbursts came forth in an uncontained, unchained torrent that began one morning like the monotonous drone of a guitar and as the day advanced rose in pitch, richer and more splendid. Aureliano Segundo was not aware of the singsong until the following day after breakfast when he felt himself being bothered by a buzzing that was by then more fluid and louder than the sound of the rain, and it was Fernanda, who was walking throughout the house complaining that they had raised her to be a queen only to have her end up as a servant in a madhouse, with a lazy, idolatrous, libertine husband who lay on his back waiting for bread to rain down from heaven while she was straining her kidneys trying to keep afloat a home held together with pins where there was so much to do, so much to bear up under and repair from the time God gave his morning sunlight until it was time to go to bed that when she got there her eyes were full of ground glass, and yet no one ever said to her, “Good morning, Fernanda, did you sleep well?” Nor had they asked her…

The rant continues with an 800-word sentence, which you can read here if you like. One thing to note is that the rant is not in quotation marks. It’s not literally her words (quotation marks suggest something is literally and truly spoken, like you would find in journalism). Instead, there’s something tricky going on with the point of view. Whose head are we in?

On one hand, the rant is in Fernanda’s voice, so even if it’s not transcribed in quotation marks, it represents her thoughts and her words, almost in a stream-of-consciousness. However, it’s simultaneously from Aureliano Segundo’s perspective, as he gradually hears this “singsong” raving. Thanks to the omniscient narrator, we can get both perspectives at the same time — Fernanda’s thoughts filtered through Aureliano Segundo’s perceptions.

As I said about the Austen above, that’s quite a narrative feat.

Up next, I’ve got a post in the works about the opposite style of more or less invisible narrators. Stay tuned.