Michael Connelly is probably my favorite mystery writer, and I recently read his newest novel, The Waiting, which is about his detective Renée Ballard with a plot line involving his classic Harry Bosch.

Because this one is around the 25th installment about Bosch and perhaps the fifth or sixth about Ballard, I would not recommend it as a first introduction to Connelly. He takes it for granted that you are somewhat familiar with all the characters, but since he doesn’t spend much time developing backstory, the novel offers some interesting insight into the mystery form.

Spoilers ahead.

Multiple Storylines, Multiple Bodies

Most mysteries have a couple of problems to solve, which you might call Mystery A and Mystery B. Sometimes, the dead body is what Hitchcock called a MacGuffin, a device that kick-starts the plot and leads you to a secondary exploration.

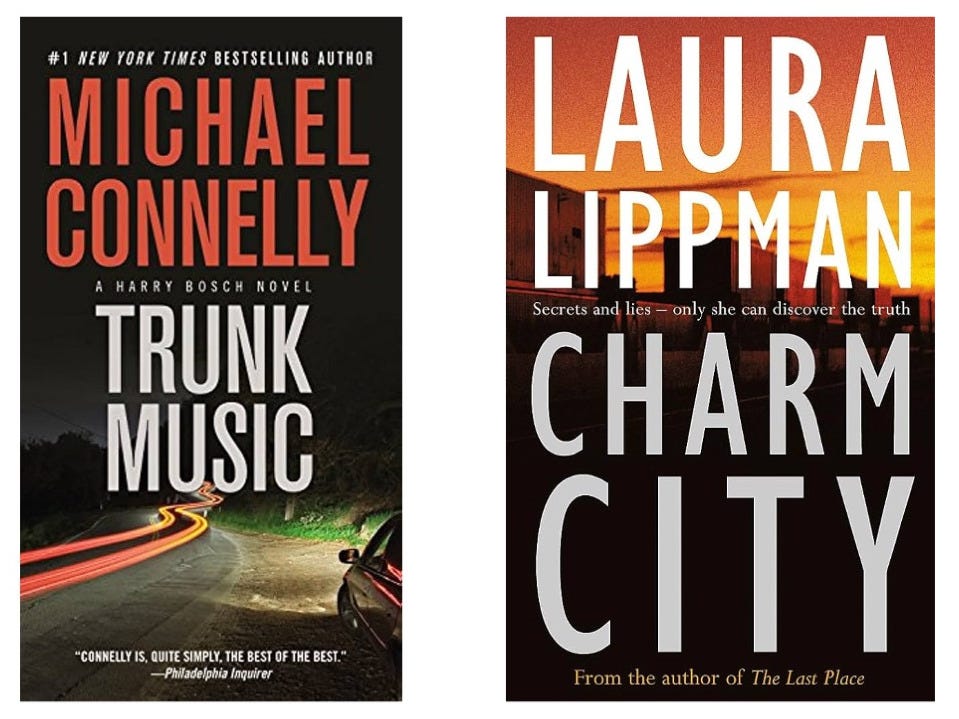

An example might be someone appears to be the victim of gang violence, which leads the detective to take down a drug kingpin — only to discover the person actually died in a lover’s quarrel. Mystery A (the MacGuffin) is the victim of the quarrel, and Mystery B (the drug plot) is a red herring to the original crime. Spoiler: This is essentially the plot of Connelly’s novel Trunk Music.

Rather than two mystery plotlines, some novels offer a public and a private storyline. Laura Lippman’s novel Charm City does this well, where she has her PI investigating whodunnit for a dead business tycoon (the public storyline) while trying to figure out what to do with a canine she inherited (the private storyline).

In The Waiting, Connelly gives us both of the above — two mystery plotlines and a private storyline for Detective Ballard. This much story might feel crowded in an ordinary novel, but with the space Connelly saves not having to develop Ballard, Bosch and Bosch’s daughter, Maddie (a young police officer now herself), he adds a third throughline to a normal-length mystery novel.

Again, spoilers, so stop here if you think you might read the book.

The first plot is the private storyline for Detective Ballard. While she’s out surfing, someone breaks into her car and steals her wallet, badge, and gun. She’s already in hot water with her department, so rather than report the theft, she sets up a whole operation to get her stuff back without her supervisor finding out. This requires the help of Harry Bosch and eventually uncovers an operation where this off-the-grid group is planning some type of mass shooting. They enlist the FBI to set up a sting involving some machine gun sales, and after a shootout, Ballard gets her badge back.

Meanwhile, she’s on the cold case squad, and they get a DNA hit on a decades-old serial rapist. Turns out, the DNA belongs to a man too young to be the killer, so they’re likely looking for his father. The only problem? His father is a big-time judge. Ballard and one of her colleagues tail the judge to get his DNA from a spoon at a restaurant — and discover his son was secretly adopted, requiring a wild goose chase to find the father.

The third plotline is a little cheesy. Bosch’s daughter, Maddie, herself a young patrol officer, volunteers for the cold case squad to advance her career, and she stumbles on a cache of murder photos in a storage unit — and the serial killer likely was responsible for the infamous Black Dahlia murder. They enlist a photo analyst to confirm one of these victims (unrecognizable) matches the photo of the old murdered starlet. The only problem? The DA has a beef with the police chief (who endorsed his opponent), so he won’t accept this newfangled evidence.

Storylines one and three come together because Ballard’s supervisor gets wind of her involvement with an operation with Harry Bosch — and for propriety tells her to cut Maddie loose from the squad. The only way to keep Maddie is if they can convince the DA to file charges and solve the Black Dahlia murder.

The Second Murder

One final plot device common to mystery novels is the second murder (Agatha Christie is the queen of this technique). The detective starts the investigation, goes down several rabbit holes, and it’s not until the second murder (usually around the 60-70% mark) that the whodunnit becomes clear.

In addition to three storylines, The Waiting also gives us a second murder. While chasing down the father in storyline #2, one of Ballard’s citizen volunteers takes it upon herself to question a suspect, who is a real estate agent hosting an open house. She gets murdered, which leads Ballard to the perpetrator.

So there you have it: a series of common plot patterns, all showing up in The Waiting.

(As if you needed any more drama, there’s also a minor subplot where Ballard’s mother has gone missing in the Hawaiian fires, so she’s on edge the whole book waiting for a phone call from an investigator there. It’s probably too much, and all-around over-the-top, but I found it compelling.)

Page by Page Suspense

You need “big rocks” in the structure to make a mystery novel compelling, but I might posit that suspense happens at the page level. You read a page and want to know what happens next, so you read another page. And then another. And another.

I’ve already mentioned that The Waiting, being deep into a series, gives Connelly the freedom to dispatch with much of the traditional characterization and backstory. Instead of big paragraphs of description, the book is heavy on dialogue, and dialogue tends to read faster than description.

In general, Connelly tends to reveal character through actions rather than description, but this introduction of the Bosches (father and daughter) is more economical than usual:

Maddie Bosch was in street clothes. There appeared to be no stress or sadness on her face.

“Maddie, is Harry all right?” Ballard asked.

Maddie stood up. “Uh, yeah, as far as I know,” she said. “I haven’t talked to him in a couple of days. Did you hear something?”

“No,” Ballard said. “I just thought that if you came to see me in person, there might be something—”

“No. Sorry if I scared you—that’s not why I’m here. As far as I know, Dad’s fine. He’s Harry.”

“Okay, good.”

Harry Bosch had been a mentor of sorts to Ballard and had worked with the Open-Unsolved Unit at its start. He was now battling cancer and Ballard had not gotten an update recently.

“I’m here because I want to volunteer,” Maddie said.

What do we learn about the characters from this dialogue? On the previous page, Maddie was introduced as a visitor named “Officer Bosch,” but otherwise this is it. From it, we learn she’s a patrol officer (notable that she’s now in street clothes rather than uniform); she’s taking some initiative in her career; and she and Ballard have a shared connection with her father, Harry.

We don’t know what she looks like, what color her hair is, exactly how old she is, etc., etc. We might have that information from an earlier book in the series, but Connelly leans on dialogue to keep the scene moving and assumes the reader will come along.

Maybe this scene is too spare. It might not hold your interest in a standalone novel where you don’t know who these people are or why you should care about them, but it’s a good lesson that if you’re writing suspense, you might need less description than you think.

What Happens Next?

Suspense requires more than characters chatting. You have to want to know what happens next, and one way to build that curiosity is to give the characters a task (something they want) and an obstacle.

A few chapters later, Ballard partners up with the older Bosch to get her badge back. They set up a sting where Harry is offering to sell some guns to the same crook who has the badge. Then they tail the crook, who lives in a camper, to a campsite. While the crook is hanging out by a fire pit, Ballard sneaks into the van to search for her badge, with Harry surveilling her from across the street:

She got to the white van and saw that it was completely dark inside. She went to the driver’s door and tried the handle.

“It’s unlocked,” she said. “I’m going in. You got me?”

“I see you,” Bosch said. “But I don’t think it’s a good idea.”

“He can’t see me from there and we need to know what he’s up to.”

“Still don’t think it’s a good idea.”

“Come on, Harry. You know you’d be in here if it were you.”

Ballard climbed into the driver’s seat and cautiously looked through the windshield in the direction of the circle. From this angle, she could see only one of the seated people, a woman in a folding chair with a built-in cupholder for her beer.

With Ballard sneaking around the van, the reader leans forward in suspense: Will she finally get her badge back? Will she get busted? How’s this going to play out? Again, dialogue and spare descriptions carry her into the danger zone.

Inside the van, she finds a locked box and unscrews the hinges to see what’s inside. Nothing. But then, while she’s re-assembling the box, Bosch alerts her that the guy is returning to the van and she needs to hide. She slides under a pile of blankets at the back of the van:

She reached down, slid the left leg of her jeans up, and pulled her Ruger out of her ankle holster.

She heard the voices of two men outside the van. The front doors opened and the men got in.

End chapter: A couple of short paragraphs, a gun in hand, and Ballard hiding from the crooks. It’s all basic stuff, maybe even what Raymond Carver would call a “cheap trick” if this were literary fiction, but when you see the break at the end of this chapter, you’re going to read the next chapter to see what happens.

And that’s what you want in a mystery novel.

I have such fond memories of reading Michael Connelly with my dad!