One treat of my story-reading project this year is discovering something new from an old favorite. This month I read Steve Yarbrough’s short story “Two Dogs,” which is in the Granta anthology but otherwise appears only to have been published as a limited-edition chapbook in 2000.

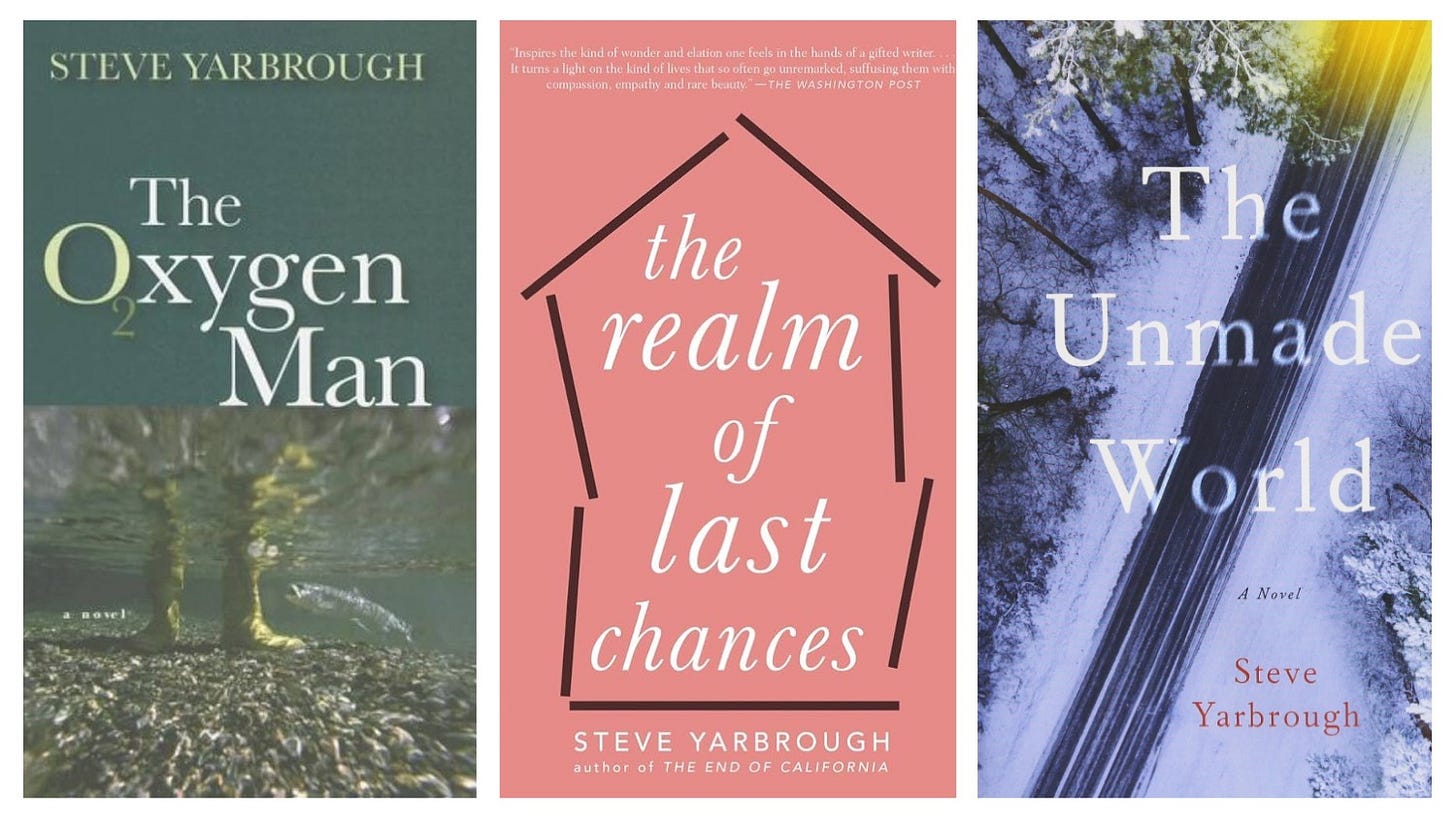

I find Yarbrough to be one of the most interesting “southern” authors working today (if you can call him that). His first few novels are gritty, spare, and set in Mississippi — very much in the Larry Brown vein of southern fiction. If you had a syllabus with Brown’s Joe, Harry Crews’s The Feast of Snakes, Chris Offutt’s The Good Brother, Ron Rash’s The World Made Straight, and Steve Yarbrough’s The Oxygen Man, Yarbrough would fit right in but he wouldn’t necessarily stand out.

However, with The Realm of Last Chances in 2013, his novels took a turn. He started writing about Boston (where he lived as a professor at Emerson) and Poland (where his wife is from), and his style shifted from “southern grit” to “omniscient realism,” more at home with Richard Yates than Larry Brown. (If you only read one book of his, I’d recommend The Unmade World.)

I say all this because I assumed Yarbrough had some kind of evolution in the mid-2000s, like he really got into high gear. Yet “Two Dogs” is in that same mode as his recent work. Since it was published in 2000, I went into it expecting a solid “southern” short story, but it took off the top of my head.

Overview of “Two Dogs”

If you can find a copy, I’d recommend reading it, but here I’ve got to summarize it to say something about it. The story has an American narrator who is married to a Polish woman, Anna. In the frame of the story, he’s sitting on a pier in Poland, talking with his brother-in-law, Tomek (who is married to his wife’s sister, Basia).

They’ve known each other for 15 years, so “There are things we both know so well that we never need to say them.” One of those things is that “a special bond exists between my sister-in-law and me.” She came to visit the narrator and Anna in California years ago and may have talked Anna into marrying him.

We learn throughout the story that the bond also has a sensual undercurrent. The narrator and Basia once shared a drunken kiss, and another time they stripped and got into a hot tub together while Anna and Tomek were away.

With that backdrop, the brothers-in-law are chatting on the pier, and the narrator, having recently come into a sum of money from Hollywood, mentions he is considering buying a place in Poland. In response, Tomek tells him a story, and much of “Two Dogs” is the story within the story.

They both know a man named Sikala, a lawyer who represented some Solidarity dissidents during the 1980s (and bought a mean rottweiler for protection). After the People’s Republic fell, Sikala and his wife purchased a place in the country for weekend getaways. They soon run into an issue with an old man’s dog next door. Their dog and his dog don’t get along.

To make a long story short, one day Sikala’s dog gets out of the gate and then brings the neighbor’s dead dog home in his jaws. Assuming his dog killed the neighbor’s, Sikala washes and blow dries the dog, drops him on the old man’s property under cover of darkness, and slinks off to Warsaw.

Later, he returns to the old man to confess what he’d done, but before he can explain, the man says he’d buried his dog in the woods. Apparently, Sikala’s dog had dug up an already dead dog. The old man, seeing the washed body of his dog back on his property, believed it to be a sign from God.

Why did Tomek tell the narrator this story? At the end, the narrator is writing all this from his home in California, and the story ends with Tomek, on the pier, saying, “I’m leaving Basia. That’s the beginning of what I have to tell you.”

The narrator asks what else.

Tomek “lays his hand on my shoulder and finishes the story.”

The end.

What’s it all about?

On the surface, there are some obvious symbolic parallels. The two dogs fighting are owned by two social classes: the bourgeois lawyer and the country peasant of the sort he represented in the Solidarity movement. Although he was on the peasant’s “side” politically, he doesn’t quite fit in:

It was true that if he’d thought about those possible neighbors, he might have idealized them as hardworking, honest farm people. He’d been guilty in the past of idealizing simple people.

Likewise, the narrator and Tomek are two other dogs circling each other. The implication is that the narrator, like Sikala, might love Poland, but he is an outsider. If he moves here, he won’t quite fit in, as the country won’t match his ideal. Another possible implication is that America, like a Solidarity lawyer, has a kind of paternalistic relationship with Poland. Americans fought the Cold War but don’t understand the actual people on the ground. (To drive that point home, there’s a reference to Graham Greene’s The Quiet American.)

A final layer of possible symbolism is that the narrator’s role in Tomek’s life is akin to Sikala’s role in the old man’s life. Sikala’s dog did something wrong — got out of the gate — but from this process, he delivered the old man a measure of peace.

Likewise, the narrator has an inappropriate relationship with Basia. Is Tomek telling him that the narrator’s transgressions helped him see his wife more clearly? Perhaps delivered a measure of peace about his decision to leave Basia? Is that what Tomek wants to tell him? Yarbrough ends the story without laying it out, so we can only speculate (or perhaps, if I reread the story, there’s a clue buried that I overlooked the first time).

There is one more moment of possible consequence. At one point, the sisters come out to the pier, and Tomek stops the story. The narrator, who is a writer, suspects Tomek doesn’t want the sisters to overhear. Or: “The other possibility — that the story is over — is one I can’t countenance. All actions — especially deceitful actions—are supposed to come with consequences attached.”

Basia tells them Anna has asked to go for a walk, which surprises the narrator, for Anna never finds it easy to talk to her sister. He writes, “I try to catch Anna’s eye, to flash her a look and ask what’s up, but she’s staring at the water as if she’s trying to see all the way to the bottom of the river. It looks as if she’s facing a task she doesn’t relish.”

What is Anna telling her sister, while Tomek is at the “beginning” of what he has to tell the narrator? Is Anna telling Basia that she will be leaving the narrator, just as Tomek is leaving Basia? Could there be anything going on between Tomek and Anna? All unexplained, yet the narrator is writing this story after the fact, “in a house which has become so still and quiet it might as well be a mausoleum.”

He has realized now, at the time of the telling, that he and his brother-in-law are like the two dogs: “You’ve seen them — you must have. Those old strays that square off against one another, circling, pawing the ground, neither one quite willing to get down to business.”

As readers, we’re not treated to the business, but we know the business happens, and the narrator is left trying to piece together the story.

Lessons for Writers?

This whole post might be an exercise in abstraction if you haven’t read the story, so I’d encourage you to try to find a copy. Writers in particular could learn a few things from it.

First, you couldn’t do this with every story, but the unexplained ending can really sink its teeth into the reader and give us something to debate.

Second, symbolism and allegory are powerful tools. Most advice books would recommend you start with the story itself, but if elements of the story can represent more than mere plot devices, all the better.

For example, Yarbrough references The Quiet American, a novel about an American CIA troublemaker and a British correspondent in Vietnam. They become involved with the same woman, kind of representing Western competition over the fate of Vietnam.

Finally, there’s nothing better than human drama. Big flashy explosions are exciting, but they don’t hold a candle to the tension of a marriage on the rocks.

From talking with writing professor friends, that might be the biggest lesson. Their students tend to write about superheroes and dragons, which might be all well and good (especially for a 20-year-old with limited life experience), but when you’re 40, you’ve been there, done that, got the T-shirt. Most of us want higher stakes.

"Big flashy explosions are exciting, but they don’t hold a candle to the tension of a marriage on the rocks." Couldn't agree more!

I enjoy his writing - great post, as always - happy Friday