The 'FOGATE' Method of Literary Criticism

Reading through the lens of Jon's old art teacher

As a reader and occasional literary critic, two concepts have influenced how I approach literature. The fancy concept is Henry James’s term donné, which he explained in his essay “The Art of Fiction”:

We must grant the artist his subject, his idea, what the French call his donné; our criticism is applied only to what he makes of it. Naturally, I do not mean that we are bound to like or find it interesting: in case we do not our course is perfectly simple — to let it alone.

Since stumbling on that quote in an American literature class in college, I’ve found it a helpful approach to reading. What is an author trying to do? And how well is he succeeding? We can’t complain that Virginia Woolf doesn’t write like Hemingway. We have to take them each on their own terms.

Looking back, however, I’d like to share a second concept that I learned from my high school art teacher, Mike Biggs. He offered the FOGATE acronym for approaching a work of art:

Focus

Open your mind

Gut reaction

Analyze

Translate

Evaluate

It’s been 25 years, so I’m not sure I have a precise recollection on the difference between “analyze” and “translate,” or “translate” and “evaluate,” but this framework is an excellent way into a work of art (or literature, or music), a way to grant a piece its donné, explore what an author set out to do, and consider her success on her own terms.

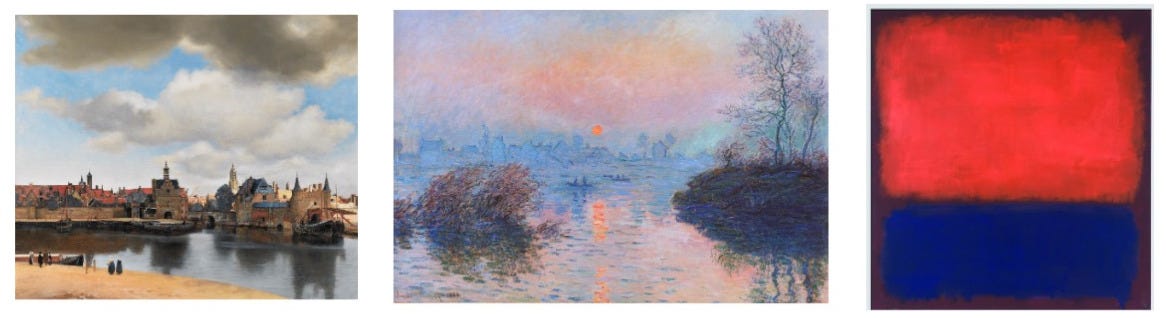

Below, I’ve applied the FOGATE method to a Rothko painting and a poem by Linda Pastan to demonstrate the framework in action.

Rothko, Untitled, circa 1950

Let’s take a look at this representative painting by Mark Rothko:

Here is how you might approach it with Mr. Biggs’s FOGATE method:

Focus. I am sitting here at my desk, with a fresh cup of Earl Grey, and a quiet house. I’ve made time to look at this painting and think about it.

Open your mind. This is a tall order for a man over 40 who has been reflecting on art for more than half his life and gotten stuck in his ways, but I’m going to do my best to withhold judgment and perform an honest analysis.

Gut reaction. My first reaction is that the painting above looks like a classic Rothko, a couple of big squares of paint. When I look at abstract art, I hear a debate in my head between the Philistine (“my child could paint this”) and the elitist (“this is great art”). A Rothko painting strikes me as art (unlike, say, a banana taped to a wall), but if I’m honest, a part of me suspects postmodernity is a joke the elites have hoodwinked the rest of us with.

Analyze. The first thing you notice is that the canvas has been painted a reddish-orange, and on the top two-thirds, Rothko has painted a large navy square. The edges of the square blur into the red-orange, and when you zoom in, you see there is a great deal of layering at work. Beneath the red-orange is a lighter yellowish layer. Meanwhile, the edges of the blue square are kind of muddy. The blue itself isn’t even a solid navy, but rather a mix of lighter and darker blues, and the colors seem to change depending on where you focus.

Translate. Staring at it up close, the whole painting seems to vibrate as the colors wash over you, the warmth of the reddish-orange, the cool of the navy. That’s interesting. I’ve heard Rotkho’s squares described as “color field theory,” so part of the project might be to call attention to our perception of color — the more you look, the more you notice. That might be one way into the painting.

Another way in: Painters often block out shapes and then add layers to refine the details. Spend enough time on a painting, and you might end up with a realistic painting in the style of Vermeer. Or, maybe you focus less on the details and more on the impression to end up with something like Monet. With Rothko, it’s as if he stepped back even further and only offer the blocked out shapes without filling in the recognizable detail.

Evaluate. What could it mean only to have blocked out shapes? Rothko is working in the postmodern era, and part of the postmodern project is to separate the representation of a thing (like a painting of a bowl of fruit) from the thing itself, so you end up with art about the making of art.

There might be an essay in the way Rothko’s painting has moved from the representation of a thing (e.g., a blue sky over a field of golden wheat) to the representation of colors — meaning the painting is “about” the psychological perception of color rather than any object being represented. In postmodern terms, the painting is about “signifiers” rather than anything “signified.”

Maybe. The challenge with art is that it’s not a math problem where a set of axioms can point you to a definitively right or wrong answer. We can’t fault Rothko for not painting a realistic bowl of oranges, so all we can do is reflect on what he’s given us and then make an argument about what might be going on.

Linda Pastan’s “Departures”

Let’s apply the FOGATE method to a poem I enjoyed recently from Garrison Keillor’s Good Poems anthology:

Departures

They seemed to all take off

at once: Aunt Grace

whose kidneys closed shop;

Cousin Rose who fed sugar

to diabetes;

my grandmother’s friend

who postponed going so long

we thought she’d stay.It was like the summer years ago

when they all set out on trains

and ships, wearing hats with veils

and the proper gloves,

because everybody was going

someplace that year,

and they didn’t want

to be left behind.

Here's how Mr. Biggs’s FOGATE method might apply to this poem:

Focus. I am sitting here at my desk, with a fresh cup of Earl Grey, and a quiet house. I’ve made time to read this poem and think about it.

Open your mind. This is a tall order for a man over 40 who has been reflecting on art for more than half his life and gotten stuck in his ways, but I’m going to do my best to withhold judgment and perform an honest analysis.

Gut reaction. It’s a short poem, with clear language, easy to read. In line 3, we see the people taking off are dying, not traveling, which is something most of us can relate to if we’ve been around long enough. The second stanza makes a turn or leap to compare the ladies’ deaths to something years ago, when they may have all traveled (or immigrated) together. It’s a poignant meditation on death.

Analyze. The poem is written in free verse, 16 lines broken into two eight-line stanzas. The first stanza introduces us to several characters who have passed away, and the second stanza makes a turn (or leap) that shifts the poem away from the present deaths to the travels of yesteryear. The poem is told by a first-person narrator (a younger family member).

Translate. Sometimes when you do the FOGATE, the steps of “focus” and “open your mind” blur together, as do the steps of “analyze,” “translate” and “evaluate.” I don’t know that there’s much to translate in this poem. In this step, you might investigate whether any meaning can be drawn from the sounds. For example, there are a lot of long O sounds (“closed,” “Rose,” “postponed going so”). You might make the case that the sound (“Oh!”) connotes a dirge.

Evaluate. What’s it all add up to? It’s a nice metaphor — death like boarding a ship — because it gives us a window into this character’s family. Where were these ladies going when they boarded ships and trains? It sounds like they were immigrating, and they were all going one after another, perhaps from the Old Country to America. Perhaps they were chasing a better life, and perhaps they found it since they all made it to old age.

In the last line, the narrator imagines them dying like “they didn’t want to be left behind,” when in fact it is the narrator who is left behind, here in the new country, to tell the tale. As a second- or third-generation American (one imagines from the poem), she is losing her direct connections to the Old Country, which might add a layer to her grief. But, she’s also not necessarily alone. The “we” in line 8 implies a larger community, making the poem poignant but not bleak.

In Summary

When I sit down to read a piece of literature, I almost never go through this exact process. I do try to focus on every sentence and note the beats as the story progresses. Then, I might turn the story over in my head afterward, thinking about what the author has done, where it fits into the canon of literature, what might have inspired certain decisions.

In other words, I try to understand what exactly I just read and why the author wrote it that way. When in doubt, James’s donné or Mr. Biggs’s FOGATE methods help me move from a gut reaction (“this is exciting” or “I don’t like this character” or “the dialogue is funny” or “the paragraphs are too long”) and into something resembling proper criticism.