Over the past few weeks, I’ve written about the third-person point of view: Part 1 looked at narrators breaking the fourth wall; Part 2 looked at narrators who didn’t break the fourth wall; and Part 3 looked at stories where the narrator seemed invisible.

Today, I’m looking at Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer, a novel written in the first person but with an extended section in third. The structure of the narration reveals something about the process of writing a novel and the relationship between a narrator (or author) and his or her work.

Examining the book from the outside, The Ghost Writer is a slim volume. My copy is 180 pages, 40,000 words or so, a very short novel. It’s broken into four parts: (1) Maestro, (2) Nathan Dedalus, (3) Femme Fatale, and (4) Married to Tolstoy, which brings to mind the structure of a symphony.

One of the best reads on Roth, in my opinion, is Claudia Pierpont Roth’s biography Roth Unbound. In it, she reads The Ghost Writer as a symphony with part three being a “scherzo,” a musical form commonly translated as “joke.” You’ll see why in a moment. She also reads the novel as a küntslerroman, which refers to a book about the development of an artist. The form is similar to the bildungsroman, which is the fancy German word for coming-of-age novel.

The Ghost Writer is Roth’s first novel in a series narrated by his alter-ego character, Nathan Zuckerman, each of which is a fine study in perspective. This novel opens:

It was the last daylight hour of a December afternoon more than twenty years ago—I was twenty-three, writing and publishing my first short stories, and like many a Bildungsroman hero before me, already contemplating my own massive Bildungsroman—when I arrived at his hideaway to meet the great man. The clapboard farmhouse was at the end of an unpaved road twelve hundred feet up in the Berkshires, yet the figure who emerged from the study to bestow a ceremonious greeting wore a gabardine suit, a knitted blue tie clipped to a white shirt by an unadorned silver clasp, and well-brushed ministerial black shoes that made me think of him stepping down from a shoeshine rather than from the high altar of art.

What do we make of this from a craft perspective? It’s in the first person, telling a story twenty years ago, so the psychic distance is somewhat removed. Our narrator, whom we soon enough find out is Nathan Zuckerman, is erudite and holds capital-L Literature in the highest esteem. His hero, E.I. Lonoff, is wearing “ministerial” shoes; Literature is Nathan’s church, and Lonoff is his minister. We also suspect this novel is, in fact, the bildungsroman he hints he will one day write. We are reading his coming-of-age story that he was only beginning to contemplate. In other words, the novel is something of a metafiction, a novel about the making of fiction.

Structure of the opening

Structurally, the novel takes place over twenty-four hours in the present, with flashbacks to Nathan’s past. Part one tells the story of this evening, when he meets with Lonoff, Lonoff’s wife, Hope, and a young woman living with them, Amy Bellette. After this opening paragraph, we get a little backstory about Nathan and how he ended up here, before getting to the meat of his meeting with the great writer. The sequence carries us to page 73, a fine example of economy of scene. By economy, I mean Roth packs all the story into a short period of time; he keeps the novel tightly, almost claustrophobically, focused on this one evening.

Plot-wise, what is wrong at the beginning of this novel? What question needs to be answered? This doesn’t have a clear problem like a murder mystery, but I suppose the question is, will Nathan get what he needs out of Lonoff? Are we in fact reading the bildungsroman he was setting out to write? Does the minister of Literature bless him so that he will be able to find his individual talent?

In part one, Nathan and Lonoff discuss books, and Nathan grows more and more curious about the girl living with them. She is young, yet he finds out she is not Lonoff’s daughter: “Who is she then, being served snacks by his wife on the floor of his study? His concubine? Ridiculous, the word, the very idea, but there it was obscuring all other reasonable and worthy thoughts.”

This question of the girl’s identity pops up on page 21 of my edition, just past the 10% mark. One might read it as the instigating event, the moment the rising action occurs. Nathan’s original problem was getting blessed by the minister of Literature, but his new problem is figuring out who this girl’s identity is. A few pages later, we learn she was formerly a student now helping Lonoff organize his manuscripts. When she speaks, “Miss Bellette’s speech was made melodious by a faint foreign accent.” Who is she?

After Amy takes off, Nathan, Lonoff and his wife have dinner and discuss many things. Among them, we learn Amy is a refugee from somewhere in Europe. Then, Lonoff and his wife get into an argument. Later in the evening, Lonoff praises Nathan’s work, which sends Nathan into ecstasy. He retires to his room exhilarated.

In part two, we get a great deal of backstory about Nathan and his arguments with his father over his chosen career as a writer. In Lonoff’s guest room, he tries to compose a letter to his father to explain and justify himself. One rift between father and son is that Nathan has rejected his family and his Jewish heritage, to some degree, at least enough that his mother feels the need to ask him if he is himself anti-Semitic. The section’s title, “Nathan Dedalus,” is a clear reference to James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, who in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man rejects his own Irish Catholic upbringing and moves to continental Europe to pursue life as an artist. Late in the evening, Amy returns to the house, and soon Nathan hears a thud in the room above him. He stands on a chair to eavesdrop (as any good writer would) and overhears a melodramatic conversation between Amy and Lonoff.

The leap into third person

Part three is the magic trick of the novel, the “scherzo.” The point of view shifts to third person, and Roth treats us to Amy’s story, or Nathan’s imagined version of Amy’s story, answering the question about her that has been raised this evening:

It was only a year earlier that Amy had told Lonoff her whole story. Weeping hysterically, she had phoned him one night from the Biltmore Hotel in New York; as best he could understand, that morning she had come down alone on a train from Boston to see the matinee performance of a play, intending to return home again by train in the evening. Instead, after coming out of the theater she had taken a hotel room, where ever since she had been “in hiding.”

In Nathan’s imagined narrative, Amy Bellette is Anne Frank, having survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and made her way to the United States. But by the time she emerges, her diary has been discovered and made public. She has become a public face of the Holocaust, and her diary and the tragedy of her death have captured the minds of the world. She now feels a responsibility to remain “dead,” in hiding, so that the public figure of Anne Frank may live on as a symbol against the forces of the Holocaust.

Roth presents this section straight, as if it is the real narrative and Amy is in fact Anne Frank, but we know it is a story Nathan has written down after being inspired by the evening. He is a fiction writer, after all, and his job is to make up stories. What’s interesting about The Ghost Writer is that, in giving us Nathan’s story within the story, Roth shows us how the mind of a novelist works.

We see the clues from parts one and two that Nathan is growing obsessed with Amy Bellette’s character, which is one way a novel begins—with an abiding image, and then a question. Amy Bellette: Who is she? Then, Roth shows us the mask of Nathan Zuckerman, narrating an omniscient story about Amy as Anne Frank. Rather than a third-person narrator breaking a fourth wall, this novel gives us a first-person narrator who disappears behind the wall.

Because the first half of the novel has introduced us to Nathan-the-narrator, we know who is narrating this third section. Since we know his predilections and his complicated relationship with his family and his heritage, we see where the story of Amy as Anne came from.

In an interview, Roth discussed his revision process for this novel. He said he had trouble writing the Anne Frank sections in third person because he kept idolizing her in the prose, holding her up on a pedestal. To solve the problem, he rewrote the section in first person, which he said allowed him to write her story more directly and honestly. He then translated the first-person version back into third, replacing I’s with she’s and such, and this process fixed the issue of voice.

The symphonic return

Part four brings us back to Nathan’s perspective. The next morning over breakfast, Hope gets into an argument with Amy and Lonoff, and then she storms off down the road. Nathan helps Lonoff into his coat so Lonoff can go after his wife, but before he goes, Lonoff says,

“You had an earful this morning.”

I shrugged. “It wasn’t so much.”

“So much as what, last night?”

“Last night?” Then does he know all I know? But what do I know, other than what I can imagine?

“I’ll be curious to see how we all come out someday. It could be an interesting story. You’re not so nice and polite in your fiction,” he said. “You’re a different person.”

“Am I?”

“I should hope so.”

The novel never really gives us an answer about Amy Bellette’s character. We are in Nathan’s head, and as he acknowledges here on the last page, all he knows is what he can imagine. He imagines her as Anne Frank, but that’s all we as readers can know as well.

We do, however, get the answer to the novel’s other opening question. Here, Nathan has gotten the blessing from the minister of Literature. Lonoff gives him permission to write the story, which gives him permission to call himself a Writer. By eavesdropping on his host and then writing the story of Amy as Anne, Nathan has earned the blessing he came for.

And we, the readers, are treated to an inside look at the mind of a novelist. We see where stories come from and how a novelist executes. We see the importance of doubt when Nathan asks, “But what do I know, other than what I can imagine?”

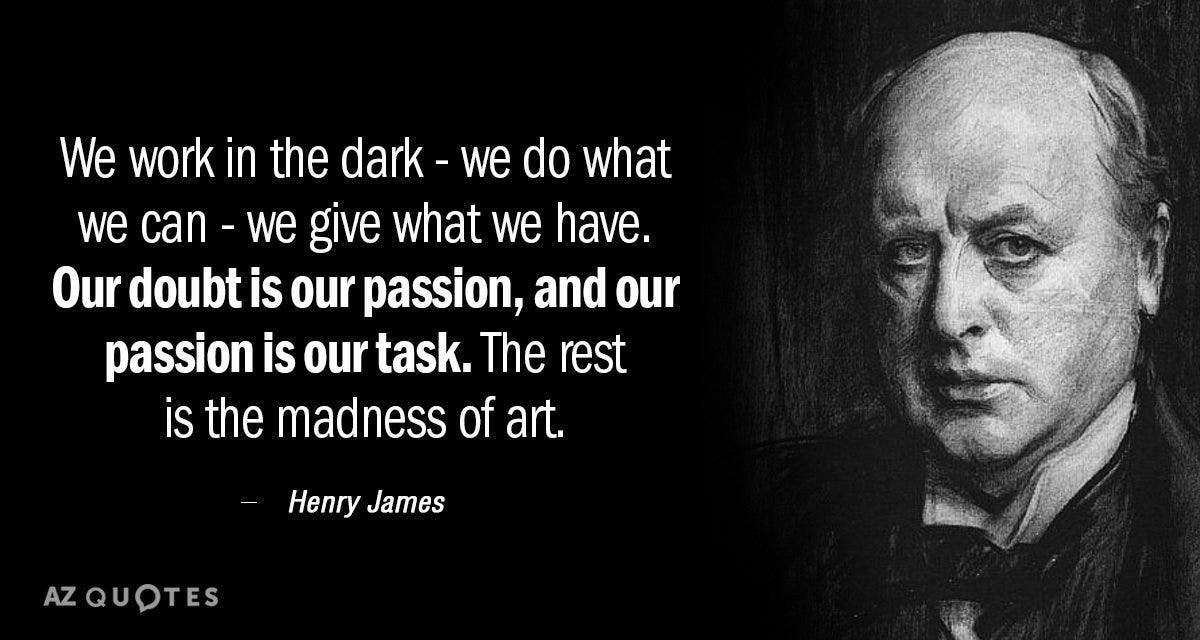

There is one additional literary reference running through The Ghost Writer, which is that Nathan loves Henry James’s story “The Middle Years,” and he references a quote from that story. James writes, “We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

That is a fine motto for anyone interested in the art and craft of being a novelist.

Great breakdown on POV shifts. I’d not heard Roth’s interview on rewriting the third section to fix the voice.