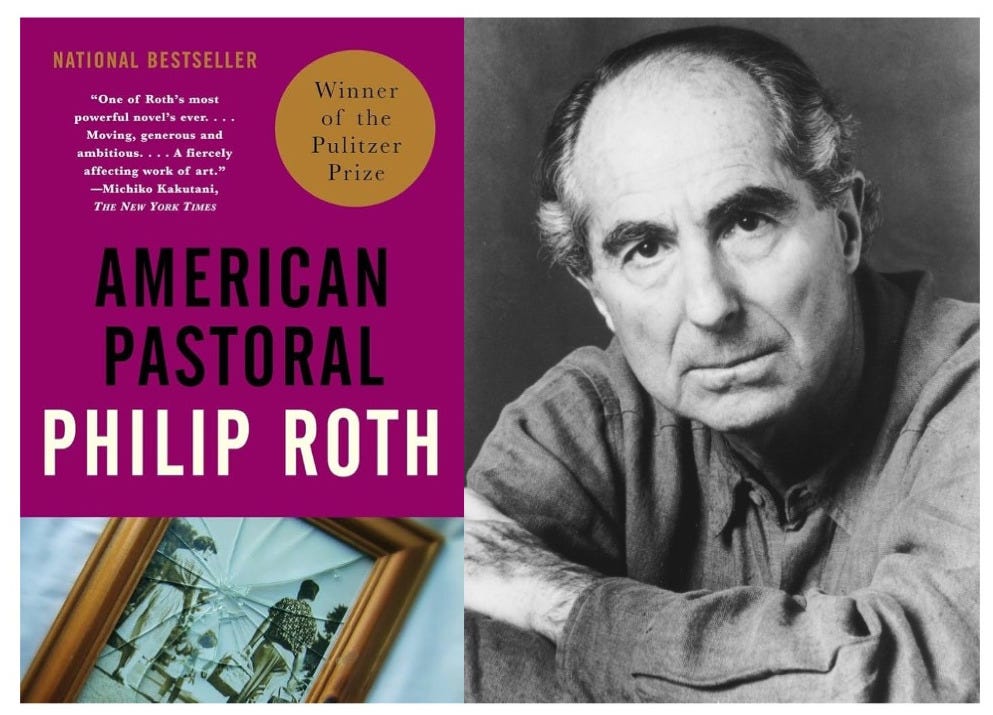

Last week I wrote about point of view in Philip Roth’s novel The Ghost Writer. This week, I’m excited to discuss one of my favorite books from one of my favorite authors, Roth’s American Pastoral, another novel in which he uses his alter ego Nathan Zuckerman as a filter for the main character’s story.

Whereas The Ghost Writer breaks down to about 75% first-person from Zuckerman’s perspective and 25% the third-person story he narrates, American Pastoral opens with about 20% from Zuckerman before he disappears into the third-person analysis of the Swede Levov.

The Swede is the older brother of one of Zuckerman’s childhood friends, a neighborhood athletic legend who grew up to marry Miss New Jersey, inherit his father’s glove-making business, and live an all-American life in the conservative town of Old Rimrock, New Jersey.

This idyllic life gets shattered, however, when his daughter, Merry, afflicted with a stutter and raging against the Vietnam War, gets swept up in the radicalism of the 1960s and blows up the local post office. She goes on the lam, and the Swede spends the rest of the story trying to figure out where she went and what went wrong in his life.

According to Roth’s biographers, in the early 1970s he originally wrote about 75 pages of a story focused on Merry, and then he spent 20 years turning that story over in his head until he eventually had the bright idea of shifting the focus over to the Swede.

Enter the Narrator

At the time of the telling, Zuckerman is in his early 60s, a successful novelist now living reclusively in the Berkshires like his hero I.E. Lonoff in The Ghost Writer. Out of the blue he receives an invitation to lunch with the Swede, ostensibly for help writing about the Swede’s father and his reaction to the family’s tragedies.

Zuckerman is excited to learn something about his childhood hero and what might be going on inside the man’s head: “Only…what did he do for subjectivity? What was the Swede’s subjectivity? There had to be a substratum, but its composition was unimaginable.”

This is great insight into the life of a writer. Serious fiction writing starts with just this kind of interrogation, the curiosity to understand someone else’s inner life.

Over lunch, however, the Swede reveals nothing, instead prattling on about his three sons and, when pressed, his brother Jerry. He makes no mention of Merry or the bomb, leaving Zuckerman flummoxed:

The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong. Maybe the best thing would be to forget being right or wrong about people and just go along for the ride. But if you can do that — well, lucky you.

A few months later, at his 45th high school reunion, his old friend Jerry, now a blowhard surgeon living in Florida, informs Zuckerman that the Swede had been sick with cancer during that lunch and now he was dead. He also fills Zuckerman in on Merry, which kicks up Zuckerman’s imaginative juices and sends him into a revelry right there during the reunion. While dancing with an old flame to Johnny Mercer’s “Dream,”

I dreamed a realistic chronicle. I began gazing into his life — not his life as a god or a demigod in whose triumphs one could exult as a boy but his life as another assailable man—and inexplicably, which is to say lo and behold, I found him in Deal, New Jersey, at the seaside cottage, the summer his daughter was eleven, back when she couldn’t stay out of his lap or stop calling him by cute pet names…

And that’s the last we see of Nathan Zuckerman, at least explicitly. His voice is in control of the narrative for the next 300 pages, a mediating consciousness, but the rest of the book is told in straightforward omniscient prose as the Swede goes chasing after his lost daughter.

Why Nathan Zuckerman?

A few weeks ago, I discussed Ian McEwan’s Atonement, in which we learn the entire novel has been an act of atonement by the narrator, Briony Tallis. The twist in the end reframes the entire novel. In American Pastoral, Roth introduces the narrator upfront but provides no clear reason why we need a Nathan Zuckerman to carry the story.

There are some parallels between the two men. Like the Swede, Zuckerman is afflicted with prostate cancer (though his is not terminal). Unlike the Swede, and unlike most of his classmates at the reunion, he has no children or grandchildren. He’s entered old age, looking back, and perhaps is baffled by the counter-narrative of the Swede, the tragic turn his ascendant hero’s life took.

Ergo, you could argue Zuckerman is a foil to the Swede in the same way Nick Carraway is a foil to Jay Gatsby, the everyman we relate to who writes about the larger-than-life figure incapable of telling his own story.

Zuckerman gives us plenty of reasons he is interested in the Swede, and he’s an interesting character himself, so maybe that’s reason enough to structure the book the way he does. Roth’s narrator becomes obsessed with the Swede, and we’re along for the ride with him, but there’s another reason it makes sense for Zuckerman to introduce this novel: the problem of consciousness.

Roth has been compared to his friend John Updike, who chronicled the middle-American everyman in his Rabbit novels. Unlike Roth, Updike launches straight into the story of Harry Angstrom, no filter needed. Roth could have done the same for the Swede, but unlike Updike, he’s a much cagier author. He’s always looking around corners, stepping back to reevaluate, asking why, why, why. He also flirts with the line between fiction and reality so that you don’t know where the author ends and the story begins. See, for example, Operation Shylock, Deception, or The Facts.

Via Nathan Zuckerman, he brings us into that process, so that American Pastoral is a dual narrative, the Swede’s bafflement over his daughter and Zuckerman’s bafflement over the Swede. The Swede, in Zuckerman’s telling, has a rich inner life, but he’s not an introspective man. He’s at his happiest when he is giving tours of his glove factory, discussing the procedures and operations of his business. He can barely ask the questions about what went wrong with his daughter, whereas Zuckerman has an endless well of questions about the Swede. As he puts it,

He’d invoked in me, when I was a boy — as he did in hundreds of other boys — the strongest fantasy I had of being someone else. But to wish oneself into another’s glory, as a boy or as a man, is an impossibility, untenable on psychological grounds if you are not a writer, and on aesthetic grounds if you are. To embrace your hero in his destruction, however — to let your hero’s life occur within you when everything is trying to diminish him, to imagine yourself into his bad luck, to implicate yourself not in his mindless ascendancy, when he is the fixed point of your adulation, but in the bewilderment of his tragic fall — well, that’s worth thinking about.

At its heart, American Pastoral is about answering the unanswerable, not just about why life takes its tragic turns but what goes on inside the mind of another human being. What can we know about others? Can we know anything? Why do they handle tragedy this way? Could anything have worked out differently? How should we live ourselves? How do we know? Can we know? Does any of this add up to anything? Does it matter?

These are my questions paraphrasing Roth writing Zuckerman interrogating the life of Swede. We don’t get many answers, but that’s the point. The Swede’s daughter, like much of America, went berserk in the 1960s, and then time moved on without providing any answers. Here we are in the 1990s with Philip Roth (or on our own in the 2020s) trying to figure out what country we live in.

Biographical Tidbits

There’s too much to say about the rest of American Pastoral, so I’ll close with a quick blurb from Blake Bailey’s big biography of Roth. Roth cribbed the name “The Swede” from a star athlete from his neighborhood. Allegedly, he’d never met the real Swede and didn’t know anything about him. When the book was published, however, the real Swede reached out for an autograph. Turns out, his name was also Seymour, and he also married a gentile beauty queen.

The easy explanation is that Roth had heard some of those details over the years and forgotten them, but it also wouldn’t surprise me if the character he made up innocently had a real-life counterpart. That feels like a Rothian moment, and perhaps why Norman Mailer once called fiction writing “the spooky art.” Bailey notes it reminded Roth of Flaubert’s observation, “Everything one invents is true, you may be perfectly sure of that. Poetry is as precise as geometry.”

Thanks as always for these close looks at shifting POVs, the hardest technique for most writers to master.